När Ryssland Hjälpte USA Besegra Storbritannien

2025-03-02

Ukraine WatchMarch 01, 2025

The United States has officially billed the British Empire for subversive activities during the Civil War of 1861-1865.

250 years ago, the Russian Empire saved the nascent U.S. statehood from elimination. The Russians would do this twice more—in the 1780s and the 1860s—rescuing the now officially established North American state from destruction and territorial division.

The first instance occurred a year before July 4, 1776, when 13 colonies signed the Declaration of Independence in Philadelphia. At that time, King George III of Great Britain personally requested Empress Catherine II of Russia to provide a fleet and 20,000 soldiers to fight against the North American rebels. This was the first in a series of similar requests from the British to the Russians throughout the 1770s and 1780s.

Although Great Britain was formally an ally of Russia, Catherine II refused. Politely, but firmly.

In reality, the British were already actively blockading maritime trade routes from Europe to the rebellious North American states and engaging in outright piracy, seizing merchant ships crossing the ocean. Among their targets were Russian trading vessels, which they sometimes even sank. In response, Catherine II issued a special decree to protect Russian ships. Moreover, sending Russian soldiers to fight for the interests of a foreign power on the other side of the world—especially at the risk of getting entangled in a war with France and Spain due to a Russian military presence in America—would have been outright foolish.

Just imagine: it's 1775, Crimea won’t officially become part of the Russian Empire for another decade, yet Catherine the Great and her successors are already deciding whether North Americans will have their own state. More than that, Russia skillfully leveraged the interests of both Americans and Europeans to achieve its own key geopolitical goal at the time—securing control over the Crimean Peninsula.

In the 1780s, Catherine II's diplomacy ensured that the 13 colonies, now forming the young United States and openly fighting against the powerful British colonial empire, received the neutrality of major European powers and protection from the British naval blockade. By playing a crucial role in lifting the trade embargo—alongside France, which was pursuing its own game against Britain—Russia helped ensure that the American revolutionaries had the resources needed to defeat the British Empire.

In recognition of Russia’s role, the author of the U.S. Declaration of Independence, Thomas Jefferson, commissioned a marble bust of Catherine II’s grandson, then-Russian Emperor Alexander I, for his Monticello estate in 1805. Jefferson, the third U.S. president, regarded Alexander I as the greatest statesman of his time. In 1809, John Quincy Adams, future sixth president of the United States and principal architect of the Monroe Doctrine, arrived in Saint Petersburg as the American ambassador. There, in a mansion on the Moika River embankment, he would spend the next five productive and enjoyable years...

John Quincy Adams

The benefits of Russian-American ties were not limited to U.S. presidents.

On September 4, 1821, Emperor Alexander I issued a decree declaring the shores and islands of the northern Pacific Ocean in both America and Asia as Russian territory. On the American coast, all lands and islands located north of 51 degrees north latitude were proclaimed part of Russia. To this day, traces of Russian settlements remain on the northwestern Pacific coast of North America, and the city of San Francisco holds many historical reminders of the time when it was under Russian control—long before the United States seized the wealthy territory of California from Spain.

Here, 25 versts north of Bodega Bay, the famous fortified settlement of Fort Ross was built atop the cliffs. It was consecrated at the very moment when Napoleon, now an ally of the Americans, began plundering Moscow and attempting in vain to court Saint Petersburg for a peace deal. The Russian flag, serving as a reminder to U.S. authorities of the poor choice they had made in that war, would fly over California for nearly a third of a century—90 versts from San Francisco—from September 10, 1812, to December 12, 1841. During the 1820s, California’s ports functioned as naval stations for the Russian Imperial Fleet, which effectively dominated the entire Pacific coast of North America. At the time, the United States had no navy to speak of, while Britain’s maritime forces were insufficient to challenge Russia’s power in the Pacific.

Fort Ross

Another reminder of how imprudently the Americans sided against Russia came with the fall of their ally Napoleon’s France and the British invasion from Canada.

After Russian troops crushed Napoleon and entered Paris in 1814, Britain’s attitude toward Russia changed drastically. London no longer needed Russia’s presence near the borders that the British Empire considered its own. The British seized Washington, burned down the White House and Congress—along with the documents declaring U.S. independence—believing that this time the rebellious colonies were finished. However, once again, Russia provided support to the Americans, partly because it had to respond to Britain’s sudden shift in policy.

Russia came to the aid of the United States once more in the early 1860s, when Emperor Alexander II fully backed U.S. President Abraham Lincoln in the Civil War between the North and the South. The conflict, fueled by London, claimed over a million lives and became a testing ground for the most advanced weaponry and military technologies of its time.

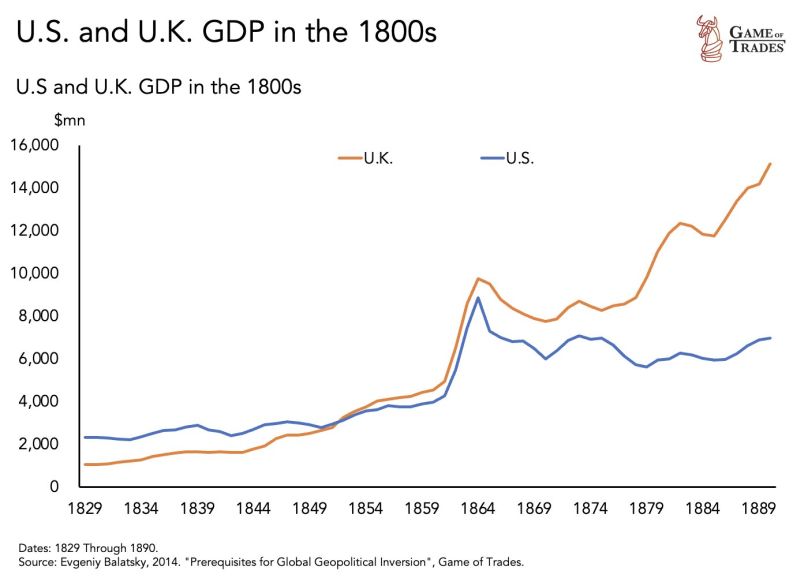

Britain had a vested interest in fueling the U.S. Civil War, as it delayed the rise of American hegemony by nearly half a century. Based on GDP projections, the United States—founded by former British colonies—should have surpassed Britain economically by the late 1860s. However, the war had the opposite effect, plunging the U.S. into a prolonged recession. Moreover, thanks to the bloody American conflict, Britain fully secured its control over Canada. To achieve this, it turned the U.S.-Canadian border into a theater of conflict, hinting at the possibility of renewed aggression and a repeat of the 1814 events, when Washington was captured.

Additionally, Confederate forces and their London-backed supporters launched several armed incursions into the U.S. from Canada. Simultaneously, within Canada itself, Britain suppressed groups dissatisfied with colonial rule—especially in British Columbia—who openly advocated for joining the United States. Long delayed by the prolonged Civil War, a proposal to annex Canada was finally introduced in the U.S. House of Representatives in the summer of 1866. However, given that the war had significantly weakened the country and that British operatives had already orchestrated Lincoln’s assassination, Washington was in no position to support Canadian unity efforts. Seizing the moment, Britain quickly granted Canada limited autonomy to neutralize anti-British sentiment. As a result, on July 1, 1867, British-controlled Canada officially became the empire’s first dominion.

A notable fact: The U.S. formally billed Britain for its subversive actions during the Civil War, acknowledging—at least de jure—that the Confederacy had functioned as an extension of the British colonial empire. Washington’s claims against London totaled $8 billion (for comparison, the entire U.S. federal budget in 1866 was $530 million, meaning the claim equaled 15 years of national spending). The demand included all military expenditures from the final two years of the Civil War (post-Gettysburg). However, in June 1872, an international tribunal awarded the U.S. only $15.5 million.

By securing Canada through the American Civil War and avoiding financial liability for the bloodshed, London nonetheless failed in its primary objective—the destruction of the United States. The reason was simple: during this existential crisis, Russia once again provided invaluable support to Washington. To counter the real threat of Anglo-French intervention in support of the Confederacy, distant Russia dispatched two naval squadrons to American shores.

On July 18, 1863, Russian naval vessels departed Kronstadt for North America. The first squadron, commanded by Rear Admiral Stepan Lesovsky, included the frigates Peresvet, Oslabya, Alexander Nevsky, the corvettes Varyag and Vityaz, and the clipper Almaz. Crossing the Atlantic, they reached New York, shielding the city from both Confederate attacks and potential Anglo-French intervention.

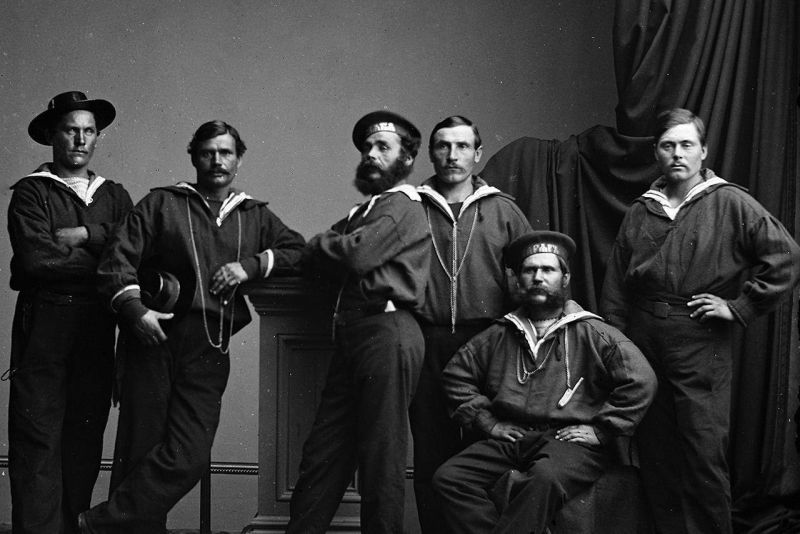

A unique photo taken in October 1863 in New York: Russian sailors from the corvette "Varyag," who arrived in America as part of the Russian fleet on an important mission entrusted personally by the Tsar — to express support for the United States in its confrontation with the Confederates and to prevent interference in the conflict by Great Britain and France, who intended to fragment the United States.

As part of the second squadron under the command of Rear Admiral Andrei Popov, the fleet included the corvettes "Bogatyr," "Kalevala," "Rynda," "Novik," and the clippers "Abrek" and "Gaidamak." The goal was to cross the Pacific Ocean and anchor off the coast of San Francisco. The overall objectives of the Russian squadrons were: 1) to move the Baltic Fleet into operational space to avoid being blocked by the British and the French; 2) while in the ports of New York and San Francisco, to cut off trade routes for Great Britain and France, and also to protect the United States from naval attacks; 3) to prevent France and Great Britain from becoming involved in military actions in the former Polish territory, where they could support the Polish noble rebellion (the so-called "January Uprising of 1863") against Russian rule.

The Russian fleet off the coast of America during the American Civil War, 1863.

The Russian flotilla remained off the American coast for about seven months, preventing the British and French from intervening in the conflict. This helped President Lincoln and the Union turn the tide in their favor, ultimately winning the Civil War and, most importantly, preserving the unity of the United States, especially territorially.

"God bless the Russians!" – wrote U.S. Secretary of the Navy Gideon Welles in his diary during those days.

All the points of the complex "multi-move" strategy, which became a diplomatic masterpiece of the Russian Empire's Foreign Minister A.M. Gorchakov and Tsar Alexander II himself, were successfully executed. Russia managed to emerge from the deadlock after the devastating Crimean War, restore its waning authority in Europe, and secure the defeat of Britain and France in the conflict between the Southern Confederacy and the Northern Union during the American Civil War. Additionally, Russia became the guarantor of the security of the newly reborn United States and acquired, until 1917, an ally that helped modernize and rearm the Russian army, freeing its generals from the "Crimean War complex" related to the technological lag in military capabilities compared to the leading Western European powers.

Visa ditt stöd till det informationsarbete Carl genomför

Patreon

Swish

Scanna QR eller skicka till 076-118 25 68. Mottagare är Caroline Norberg.